Professor reveals Filipino caregivers in U.S. vulnerable to exploitation during pandemic

New research shows lack of labor protections for Filipino caregivers is exacerbated with COVID-19 crisis

San Francisco State University Associate Professor of Sociology Valerie Francisco-Menchavez recently authored a research paper with a personal story attached to it. “I attribute my grandmother’s early death to the stress she had as a caregiver,” she said.

This connection was one of the reasons Francisco-Menchavez decided to conduct research on caregivers for the elderly and their challenges, particularly during the COVID-19 crisis. Specifically, she wanted to look at the experiences of Filipino caregivers — like her grandmother — who largely make up the number of practitioners in the field. And there’s a reason why they do: The Philippines has a sophisticated system of exporting labor to other countries, Francisco-Menchavez explains.

Historically, many Filipinos who leave the Philippines do so for jobs that address labor shortages in other countries, acting as migrant workers. They often do this to earn higher wages abroad, allowing them to send money to their families in the Philippines. With the pressure to financially support their family members, many of these workers will take jobs without understanding the dangers they may present, Francisco-Menchavez says. Her research shows that this is a common story for Filipino caregivers in the U.S. during the pandemic.

“If they don’t work, they don’t have something to send home to the Philippines,” she said. “So they will walk willingly into a caregiving job with minimal personal protective equipment and without knowing the full extent of the pandemic or the virus because they have people who rely on them in the Philippines.”

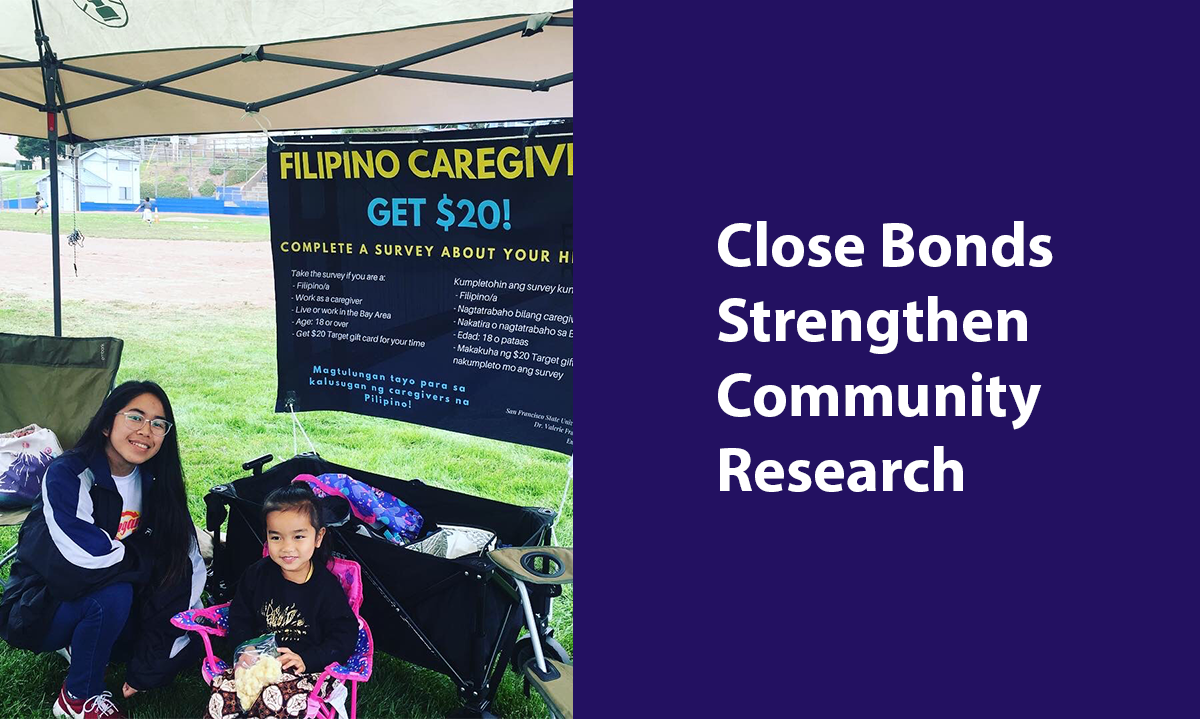

Francisco-Menchavez and research collaborator Katherine Nasol, Ph.D. student at the University of California, Davis, interviewed and surveyed Filipino caregivers in the U.S. to get a deeper view of their experiences before and during the pandemic. The collaborators published their findings in the journal American Behavioral Scientist last month.

Even before the pandemic, home care workers and their health were often at risk because of how physically strenuous it can be assisting patients with common daily activities, such as getting up out of bed, laying down or getting on and off the toilet. For example, 64% of respondents said they felt persistent pain in their bodies.

And when the pandemic first struck, residential care facilities for the elderly were common sites for COVID-19 outbreaks, putting caregivers’ health at more risk. A shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE) at the time also exacerbated the issue.

“Well, they provided us with PPE, but only very minimal,” one survey participant said. “Like four pieces only, and then ... they just told us to spray them with disinfectant and reuse it again.”

Findings also show that some participants did not seek government assistance during the pandemic because it could’ve jeopardized getting a green card.

“I cannot apply for a housing assistance because right now, if you are going to apply for any government aid or government assistance, you will not be granted a green card because of that,” another participant said. What she is describing is a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services rule enacted in 2019 that made it more difficult for immigrants to obtain a green card if they use public benefits.

SF State junior Alyssa Barquin helped conduct interviews for the study. A Filipina American, she said she was glad to take part in a project that amplifies the voices of the Filipino migrant worker community.

“They’re very much invisible frontline workers, and through the interviews we see that they experienced a lot of physical abuse and mental abuse,” Barquin said. “But they are not passive recipients of oppression. They very much want to use their voices, even if it looks like they can’t.”

Barquin, a Sociology and Asian American Studies double major, also said the research was a great learning experience for both disciplines. “This research is like the perfect marriage between Sociology and Asian American Studies because we’re taking a sociological analysis for an Asian American group,” she said. “I’m really glad that I found this project.”