Revzina and her family — including daughter Julia, then 10, and husband Lev — were part of a wave of Russian-Jewish emigrants in the 1990s admitted to the United States as political refugees due to overt, institutionalized anti-Semitism in the former USSR. “Very dirty, very poor, no food, nothing,” is how Revzina sums up the Yeltsin-era Russia she left behind. In addition to empty store shelves, there were limited opportunities, in particular for Jews, who were kept out of more upscale professions like medicine by being excluded from those university training programs. Revzina, who felt called to the medical arena, studied civil engineering and worked as a researcher until her U.S. journey began.

“I cried because I thought, gosh, it’s a very clean country, it’s beautiful surroundings and it’s excellent people,” she says, animated with the emotions of the day more than 20 years later. “This is absolutely my country.”

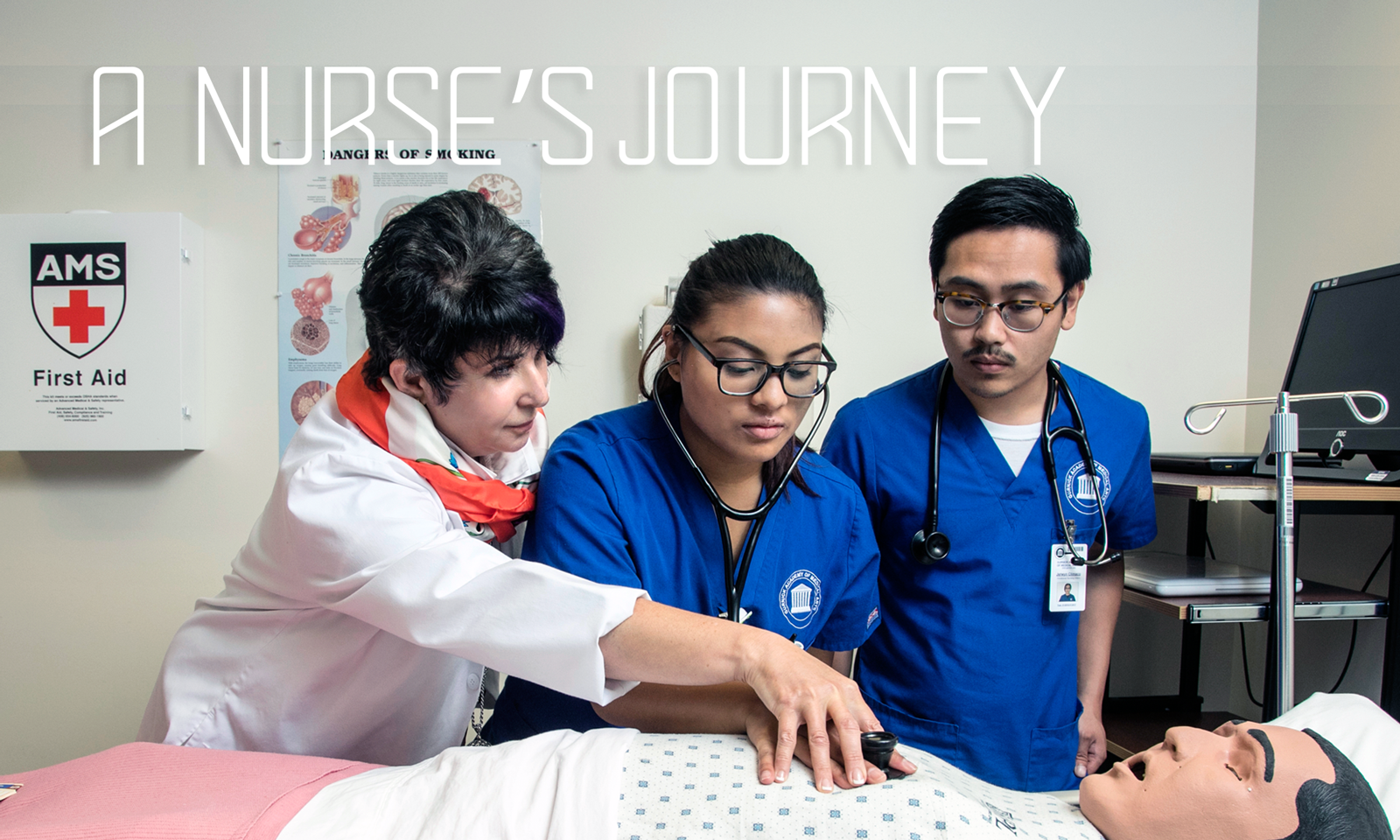

Revzina embraced her American life, and a success story unfolded. She earned her M.S. in nursing science at SF State, and returned to school for her nurse practitioner certificate. After several years of clinical practice, and some teaching in SF State’s nursing program, she co-founded the Gurnick Academy of Medical Arts, a nationally accredited professional training school where she is currently the chief academic officer. Her resume suggests a straight line to success, but the reality was a meandering path of struggle, poverty and a particular penchant for turning failures into opportunities.

Navigating an educational maze

As a new arrival, Revzina had neither the language nor the money to attend medical school. So after a few months of English lessons arranged through the local Jewish center, she enrolled in Foothill College, having heard through the Russian-immigrant community that dental hygienists earned a good living (“$30 an hour — a million dollars!” she thought at the time). She slowly made her way through a maze of prerequisites and unclear outcomes, only to miss the cut for limited internship slots by just one place on the list. She was crushed. “You cannot imagine the amount of tears and screaming and crying,” she said of watching three years of struggle amount to “no job, nothing.”

But the effort would amount to something, after all. A friend from the dental program encouraged Revzina to look into nursing. She found SF State’s Generic Master’s Program in Nursing Science, which did not require applicants’ undergraduate degrees to be related to medicine. There were still prereq’s, but with her engineering degree and her health-related Foothill coursework, she easily qualified.

Day One at SF State set a lasting tone. Patricia Hess, a now-retired professor, did a role-playing exercise, assigning students to don doctor, nurse and patient roles. With her choppy English and the social chasm between her and the other students — well into her 30s by now, she was the only older student — Revzina tried to hide. But Hess wouldn’t allow it. “She said to me, ‘You’re going to be a doctor,’” and made Revzina stand her ground in the exercise. It was a pivotal moment; Hess’ refusal to let her disappear forced Revzina to own her education and imagine a promising future.

Years later, when Revzina earned her doctorate in education from the University of San Francisco, one of the first calls she made was to her former mentor. “Dr. Hess? This is Dr. Revzina!” she belly-laughs, recounting the moment.

Karen Johnson-Brennan, now an emeritus professor of nursing, is also in Revzina’s pantheon of influential SF State teachers — for the dubious distinction of issuing the struggling Russian student her first D, on a medicine-surgery test. Revzina marched into Johnson-Brennan’s office to seek sympathy for her special challenges of language, work and money. “Who do you want to be in life?” she recalls Johnson-Brennan asking her, not buying into Revzina’s so-called predicament. “Do you want to be a poor Russian immigrant, or do you want to be an American nurse?” She sent Revzina back home to study.

“She gave to me the outstanding lesson in life,” Revzina says of Johnson-Brennan, one she took to heart. Revzina studied harder, did well on her next test, and established a foundational no-excuses attitude that still persists today. She says her SF State teachers gave her everything. “Not a lot. Everything!” she reiterates.

“We talked many a time about strategies for improvement, which she diligently worked on,” Johnson-Brennan says of the Russian student who had trouble with exams. “She always had a positive, ‘Let's do this’ attitude.” Both Hess and Johnson-Brennan became professional collaborators, first at SF State’s School of Nursing, where Rezvina was an adjunct faculty member for a time, and later at Gurnick, doing curriculum development and part-time teaching. “She never fails to treat me as a friend and mentor rather than an employee of the Academy,” Johnson-Brennan says of their ongoing relationship. “She is one of the most dynamic, entrepreneurial women I have ever met.”

A passion for nursing

Gurnick’s humble birth story is a product of that entrepreneurialism. When Revzina’s nursing job changed to part-time, once again she needed money. Drumming up opportunity, she set up an informational interview at a very small medical training school. Her interviewer didn’t have a job for her, but he had some ideas on expanding on the medical-education model, and paid her a small consulting fee, which led to a business partnership. Their big break came a year later, when a change in the law required phlebotomists — the technicians who draw blood — to be licensed at an official school. She designed the curriculum and filed the paperwork. Five campuses, twelve nursing and imaging programs, and thousands of alumni later, Revzina says her partner enjoys joking that the $1,200 consulting fee was the best investment he made.

Thinking back to her confusing community college experience, Revzina says Gurnick’s aim was clarity. “It’s very straightforward: These are the courses you have to take; this is the certification or licensing you earn,” she says. From phlebotomy they branched out to train vocational nurses and medical assistants, imaging technicians, physical therapy assistants, and — coming full circle — dental assistants. Last year they reached a new milestone, graduating their first baccalaureate class in nursing.

As she marvels at her opportunities — and those of her daughter, who studied at two top universities and is now a senior manager at PayPal — Revzina wonders if people who were born here don’t understand how lucky they are. Back at Foothill, she cleaned houses to pay tuition. “I hated cleaning toilets. Awful. Horrible,” she says. Yet she still keeps a list of chores a client once left her, revealing both a humility and a boundless appreciation for having fulfilled that early calling to medicine. “I don’t have hobbies. Work is my hobby,” she says.