New faculty members break barriers around education

San Francisco State University is committed to ensuring its campus is a place of inclusion, and its faculty and students continue to make sense of the world through racial justice. In the College of Health & Social Sciences, new tenure-track faculty members are breaking through barriers and appreciating the home that SF State has become for so many.

Asked why he chose SF State, Assistant Professor of Child & Adolescent Development Miguel Abad says, “San Francisco State University signifies access to higher education to young people who don't have that opportunity, have been pushed out of school, been written off, or have been told that higher education is not something they could strive to get into. San Francisco State has been that place to take in young people who aren't the traditional college-going story.”

Abad is a youth worker with more than a decade of experience collaborating with community-based and nonprofit organizations in the Bay Area in numerous fields, such as college access, career development, arts education and social movement organizing.

Angela Fillingim, a new assistant professor in the Department of Sociology & Sexuality Studies, says, “Relevant education permeates the entire school culture, not just in ethnic studies — which is the heartbeat that's embraced across the campus, but with a variety of different people with varying majors, and they all still feel that sense of community.”

A Salvadoran American sociologist, Fillingim centers her teaching and research center on social justice approaches to studies of race, human rights, social theory and Latinas/xs/os.

When discussing the theme of “When I Dare to Be Powerful,” based on the above Audre Lorde quote, both faculty members have similar experiences of pressure to conform to rigid ideas of what it means to be successful as an academic and how they put in the work to get away from finding validation in dominant norms.

Abad and Fillingim agree that daring to be powerful includes focusing on how to contribute to our community and the people they try to advocate for. Abad states, “It takes a lot of intention and awareness of the spaces you are moving in and a lot of self-reflection as to why you are doing something and who you are accountable for.”

Fillingim highlighted that after leaving graduate school, students learn to ask questions that call attention to the problems they face in the communities they come from. She says that power means “you must learn to be comfortable flipping the script and being at an institution where that is valued, centered in the students, and having a space that also values that work.”

Reflecting on how they face issues of diversity, equity and inclusion in their own lives, Abad and Fillingim say their experiences make them consider their own encumbrances to the struggles others may experience. They recognize in their own lives that to overcome these hindrances, they must aim to be grounded in a community where they work to support and acknowledge each other.

“Justice will look different for everybody, but the point is that you are working together to change something, and we can agree that change needs to happen,” Fillingim says.

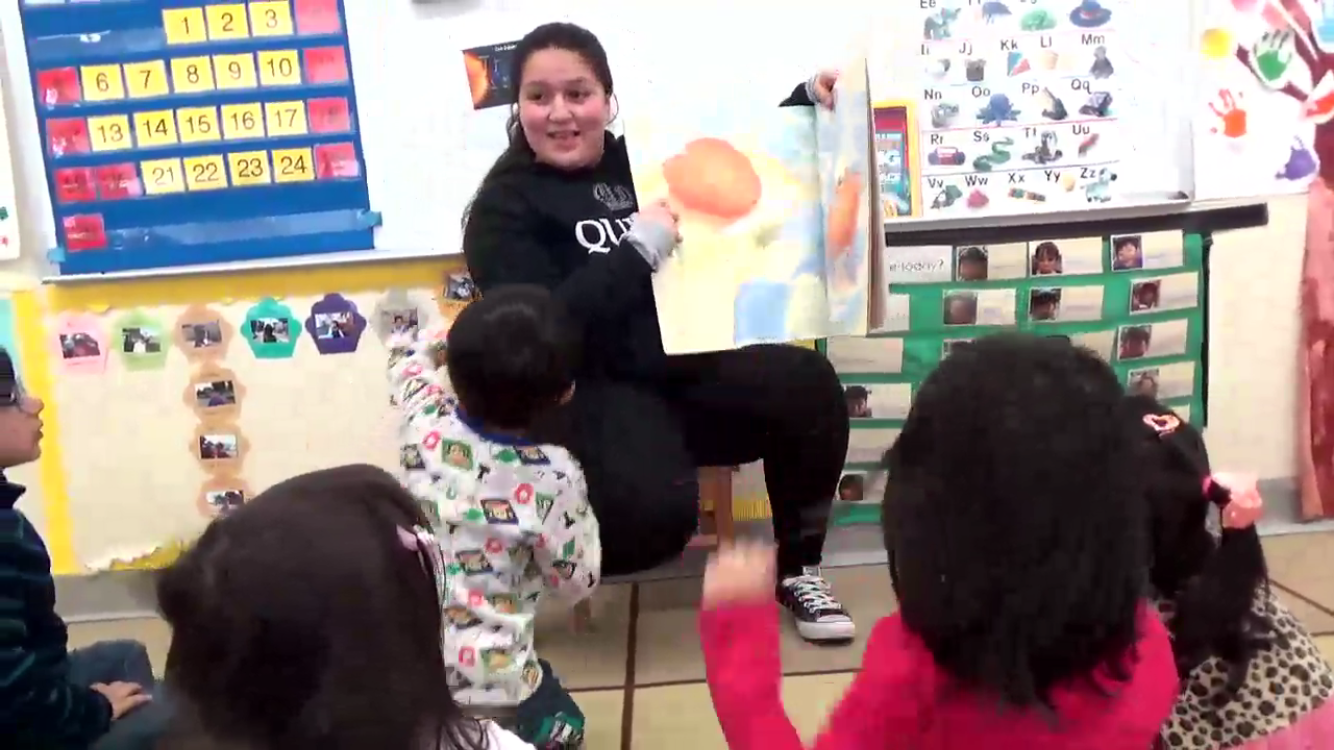

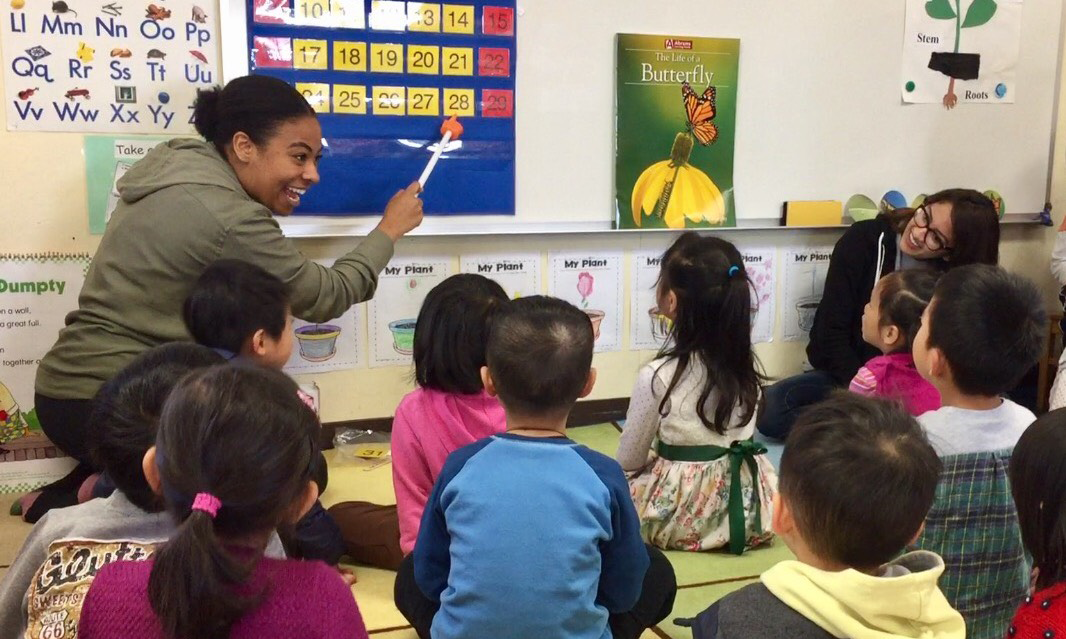

The two new faculty members emphasize the role of education in breaking barriers. Fillingim reflects on her experiences in the K-12 system that focuses on discipline and obedience instead of encouraging students to develop themselves. She can see this repetition with high schoolers she works with; many students come in with that socialization. “Focusing on education that is dedicated to understanding its students and making education meaningful to their daily lives, who they want to be as a person, and the choices they make —that is the kind of education that is revolutionary and necessary,” she says.

Abad touches on this topic with the classes he teaches, such as having his students read about Native American boarding schools and asking them to reflect on themselves and learn about or challenge their assumptions that education is always a good thing.

When working with students, whether in a college class or a community-based space, Abad tries to focus on promoting collaboration and teamwork. He is struck by students’ adverse reaction to teamwork. He says, “Not only in school but in society [students] are taught, or they come to learn that collaboration is this thing that is too hard and it holds them back as individuals or that it is this negative thing.”

“Education is a vehicle for delivering particular values, and the kinds of values I and others hope to deliver are those focused on radical transformation and social justice,” Abad says.

He recognizes the slow work of helping his students see how they are more powerful together, and how the changes they want to see in themselves and their world will only happen if they work together and express similar values.

Fillingim shares similar values about work needing to be put into the K-12 system. “There hasn't been significant change despite all this work that has been done… there needs to be thinking of education as relevant, grounded in community, grounded in self-actualization,” she says.

Fillingim and Abad both express hope that education centered on self-actualization is possible, and that through the continuous challenges we face, people are working to push through and advocate for social justice-grounded change within education.