Assistant Professor Valerie Francisco-Menchavez's team focuses on Filipino American caregivers

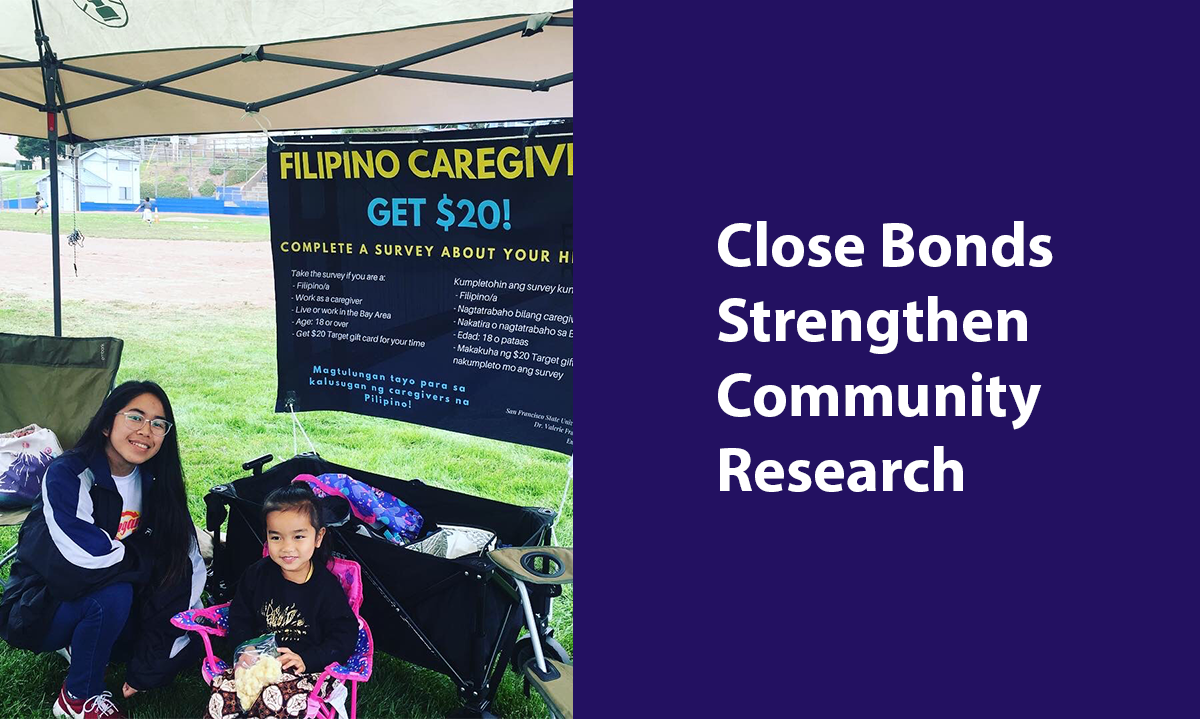

Kristal Osorio and Aya Francisco-Menchavez table to collect surveys at Kasayahan Filipino American History Month celebration in Daly City in 2019.

Before COVID-19 hit, Valerie Francisco-Menchavez, assistant professor of Sociology, and research assistants Kristal Osorio and Elaika Janin Celemen, had been hard at work preparing to present their research on Filipino immigrant caregiver stressors at the Association of Asian American studies conference in Washington, D.C. in April. But the cancellation of the conference due to the pandemic has not stopped the three women from carrying their research forward, work that is even more timely and relevant today.

“Under COVID-19, we have a new angle,” says Francisco-Menchavez. “So many Filipinos are on the front lines right now — as caregivers in home health care and nursing homes.”

The team had completed 102 surveys and eight interviews, and drafted a manuscript for publication. Now, while they wrap up the manuscript on their initial study, they are conducting new research on how the global pandemic has affected front line Filipino caregivers, especially since Filipino Americans make up a large percent of California’s health care workforce. While many work as nurses in hospitals, where they are unionized and receive benefits, others work in nursing homes and extended care facilities, or for home health agencies, where they have less protection and can experience different types of stress. For example, Francisco-Menchavez and her research team found that while many caregivers reported in written surveys that they were not experiencing stress or anxiety associated with their work, during oral interviews they revealed the opposite: many of them worried about their families in the Philippines, and experienced fears related to their immigration status and working conditions. “We need to give more attention to the precariousness of these caregivers,” says Francisco-Menchavez.

Thought partners and collaborators

As her group moves forward despite the new challenges they face, the relationship between Francisco-Menchavez and her assistants continues to strengthen and grow, even as their in-person meetings have switched to Zoom and email. “I view the students more as collaborators than research assistants,” Francisco-Menchavez explains. “They really have been thought partners and collaborators in terms of how we analyze the data we have collected. We are all working with a community we know very intimately — we all have relatives who are caregivers. So I think knowing that puts so much of my trust into them.”

Osorio, a senior who is also a community organizer, says she appreciates Francisco-Menchavez’s community organizing background and the fact that she doesn’t focus on mistakes, but constantly pushes her assistants to become better researchers. “She’s very straightforward in what she wants and asks really intentional questions,” says Osorio. “She’s very intentional in how she gets you to think about things you don’t normally think about, in expanding how you think about things.”

Celemen, who first met Francisco-Menchavez at the University of Portland while she was a student there, says she appreciates how the professor followed up with her, kept in touch when Celemen moved back home to the Bay Area, and offered to include her in her research project this summer. Like Osorio, Celemen says Francisco-Menchavez’s organizational skills and attention to detail have helped her understand how to take on large, seemingly overwhelming projects.

“She has such a clear idea of what we are doing; it’s all about organizing lists and agendas. Even at the beginning of our project in the early stages she set forth a whole five-month plan,” Celemen says. “She shows us how to break things down into smaller goals, in order to get to the larger goal. Seeing it piece by piece really helps when there are so many things to do, and you’re thinking, ‘what do I even start with?’”

—Elaika Janin Celemen

Both students see Francisco-Menchavez as a mentor and an inspiration. “Working with her made me realize how much work goes into becoming a professor, especially for a Filipina professor in sociology, and how much work it takes to get our stories out there,” says Osorio. Celemen says she is in awe of Francisco-Menchavez but also realizes that she is a genuine person who cares about her students as people first. “I really like how before we meet — at the beginning of every meeting — she asks how we’re doing. She cares about our well-being first.” Celemen says she was inspired by Francisco-Menchavez’s personal story, which she first learned about during the professor’s Labor of Care book tour in 2018. “I really identify with her experiences growing up as Filipino-American. She’s someone I look up to, and she’s given me opportunities to work in academia and helped me step into the real world.”

With Francisco-Menchavez’s guidance, Celemen recently began working for CREGS as a research assistant on the Together Study; she is balancing the two research projects while she takes a gap year before possibly going to grad school in public health.

— Valerie Francisco-Menchavez

Supporting and learning from each other

Francisco-Menchavez sees herself less as a mentor and more as helping two Filipinas navigate the academic world and gain skills they will need. “I’m just transferring my skills to them. I see it more as democratizing the research process. They’ve always been part of a community that looks for information systemically, that tries to answer questions in a deep and profound way. Our community has always done that and always will. We all come to the research table with strengths; I’m not the only person with skills and expertise. When I ask Kristal and Elaika, ‘What are your thoughts on this?,’ they are both empowered enough to say, ‘I think this is happening,’ or to question whether our approach is right or wrong.” She says both women are brilliant. “I really believe in them and I appreciate working with and learning from them. The experience they bring as Filipina American immigrants helps me be a better scholar, teacher, mother, parent, friend.”

Francisco-Menchavez emphasizes that her philosophy is to make sure that everyone understands that they all come to the table with unique strengths — and that together they will make the research project better. “I have skills I can train them in as a professor — academic writing and the research process, for example—but in our research group I try to break those vertical power lines and redistribute them horizontally a little more.” She says she constantly learns from her students and that their collaboration makes her work sharper and more dynamic. “I think the biggest impact is that it helps the research I do have more relevance than just being in an academic journal. Research should really belong to communities and organizations and young people and teachers; everyone should be able to access knowledge and participate.”

All three team members feel very strongly that their research not wither in academia. Some of the research Francisco-Menchavez and her students have done helped inform a report that led to state Senate Bill 1257, which gives domestic workers increased health and safety protections. Says Osorio, “Our objective is to help our community have this data and to have a better picture of how we can serve our community better or advocate for them better in terms of policy and services.”